Turbocharging for motorcycles: dawn and dusk

When it comes to the time of the birth of turbocharging, one immediately recalls the whimsical Porsche 911 Turbo and the SAAB 900 descended from heaven. Of course, the matter was not limited to these two – there were other cars and even turbomotorcycles that, with no less persistence, conveyed to the user all the delights and shortcomings of supercharging in its early iteration.

Motorcycles have learned to be incredibly fast without any turbochargers or centrifugal compressors, but the magic of supercharging haunted manufacturers before, and haunts some of them to this day. So, for example, Suzuki and Yamaha are preparing bikes with inline-two-cylinder turbo engines that promise smooth and powerful traction. But then now… Forty years ago, the “snail” was used on motorcycles not for elasticity, but for the sake of rock and roll.

The ancestor of a relatively small but bright cohort was the Kawasaki Z1-R TC, which is symbolic. Kawasaki has become famous for its completely insane motorcycles – some of its projects, such as the wild “bomber” Ninja ZX-12R and the 310-horsepower monster Ninja H2R with a mechanical supercharger and the appearance of an alien invader, were definitely born after a long libation of sake and exclamations: a-a-k … “. All the more surprising is the fact that the Z1-R TC was not a factory model, although it was sold through official dealers of the brand.

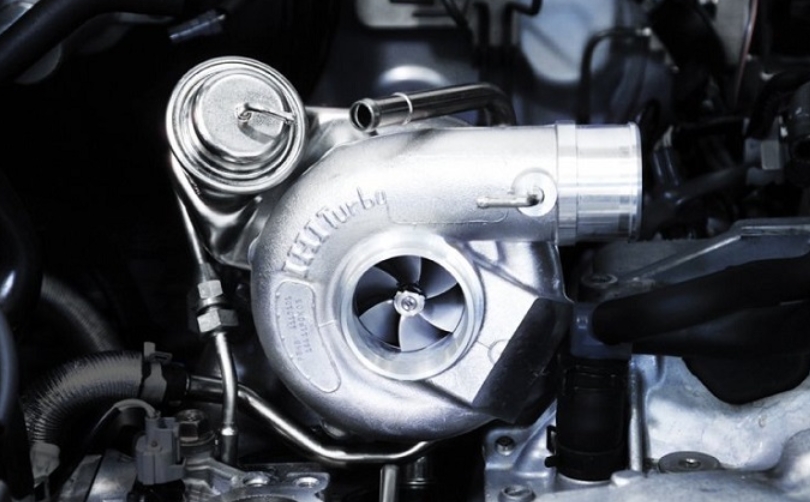

The motorcycle owes its appearance to Alan Masek, the former chief executive of Kawasaki and the founder of the Turbo Cycle Corporation. The idea to surprise the market was definitely a success. The stock exhaust manifold was replaced with a custom American Turbo Pak turbocharged one. The “snail” had an adjustable wastegate (air discharge valve), which provoked road madmen to increase the boost pressure to almost 1.4 bar, with the optimal 0.6 bar. The developers strongly discouraged motorcyclists from flirting with the boost, and they followed the recommendations like a dog that is forbidden to gnaw a bone.

1015 cc air/oil cooled engine cm developed 122 hp at 9000 rpm, which seem like a trifle at a time when any self-respecting “liter” sportbike has 200 hp in its arsenal. and more. But the whole trick was how exactly the Kawasaki delivered its power, comparable to the return of petrol car V8s of those times of crisis. He did this furiously and was clearly not recommended for inexperienced riders, moreover, willing to purchase a two-wheeled rocket without … a warranty on the engine. It really couldn’t be, although the unit was stuffed with a reinforced crankshaft, valves and valve springs. In the absence of a rev limiter, “twisting” when overdriven or out of gear led to catastrophic consequences. 500 examples were produced in 1978 and 1979, with later versions featuring slightly more refined settings.

It is believed that the potential of the engine greatly exceeded the capabilities of the chassis – just like the legendary wild-crazed “sledgehammer” Yamaha V-Max with a thin fork and a V4 engine in a “plasticine” frame. However, in reality, things were probably not so criminal and apocalyptic. “The engine delivers power very smoothly and quite early – already at 4000 rpm. The turbocharger reaches its maximum pressure at approximately 6000 rpm. The bike rides surprisingly nice and handles well,” wrote Car & Driver, an American publication that had a close acquaintance with Kawasaki, albeit with suspension modifications and Good Year Eagle HST tires.

Honda, known for its relatively friendly technology, was clearly not attracted by the concept of a “turbo sledgehammer”. She took the classic CX500 as her starting point, creating the first mass-produced sport tourer turbobike.

The first thing that attracts me about the bike is not the fairing, but the bottom-injected 498cc liquid-cooled V-twin (V-shaped, two-cylinder) engine, mounted longitudinally, like on Italian Moto Guzzis. And let the cylinder heads sticking out to the sides do not mislead you – on a two-wheeled vehicle, the layout is determined by the location of the crankshaft relative to the longitudinal axis, and in this case it is installed longitudinally.

The unit was prepared for 1.3 bar, which was pumped by a compact IHI turbine by installing a hardened crankshaft and connecting rods, as well as forged pistons, which were first used on Honda’s serial products. Turbojam was still present, and the pickup did not turn a motorcycle with a curb weight of over 250 kg into a rocket – the engine developed only 83 hp. at 8000 rpm vs. 51 hp in the atmospheric CX500, but the heavy tourer mastered 201 km / h. Nevertheless, the CX500 Turbo turned out to be an interesting and, as far as its anatomy suggests, a relatively harmonious product.

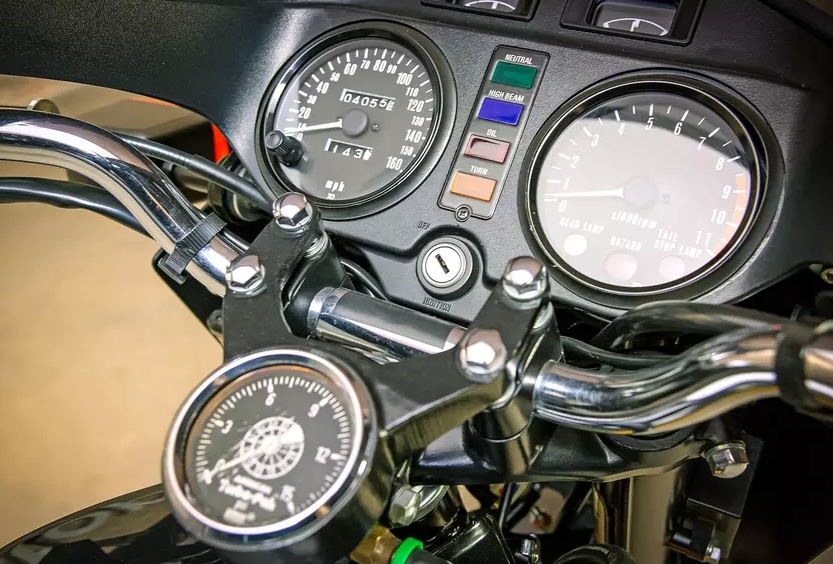

Honda did not limit themselves to one refinement of the motor and used the Pro-Link rear suspension (a linkage rear suspension system that provides progression in the characteristics of a monoshock absorber), a TRAC (Torque Reactive Anti-Dive Control) system worthy of a separate story that prevents dives during braking, and a spectacular informative instrument panel with boost pressure indicator. The frame and brakes were different.

The motorcycle was produced only in 1982 and the very next year passed the baton to the improved and supplemented CX650 Turbo with an engine whose volume had grown to 673 “cubes”. Having increased the “meat”, the Honda naturally added power to the unit in pre-supercharged modes.

The IHI turbocharger was modified – its hot part (turbine wheel) retained a diameter of 50 mm, and the cold part (compressor wheel) increased by 3 mm, to 51 mm. The pressure dropped slightly, reaching 1.1 bar, but the 100 “horses” generated by it were enough to feed the mighty Suzuki GS1100 with dust when accelerating from 100 km / h.

The CX650 was better than its predecessor – more power, less turbo lag, better “arrival”. Honda was generous with just 1,777 of these motorcycles, making them one of its rarest creations. Meanwhile, Suzuki took four years to build 1,153 XN85s. A completely different beast!

A naked look at the turbomotorcycle, produced from 1983 to 1985, is enough to understand that we are not looking at a sports tourer, but a sportbike. The semi-fairing and thick long seat, which a modern sport biker can only dream of in a nightmare, brings confusion, but clip-ons instead of a traditional steering wheel clearly hint that the XN85 is still closer to “sports”. He was the first among serial motorcycles to try on the front 16-inch wheel, which had previously only been found on racing equipment, and received a Full Floater rear suspension with a monoshock absorber. Well, the main feature, of course, was the engine – a 673-cc in-line “four” with two valves per cylinder, air cooling and fuel injection. The turbocharger increased power to 85 hp. at 8000 rpm and reminded of itself with a pickup at 5000 rpm.

There is an opinion that the XN85 Turbo did not differ in perfect wildness and its character can even be considered to some extent complaisant. Differing in driving sensations from the Honda CX500 Turbo, it showed comparable dynamics and burned ¼ miles in almost the same 12.3 seconds, showing over 160 km/h at the finish line and losing 0.4 seconds to the Honda CX650 Turbo.

Yamaha? We have not forgotten about it, and how can we forget it, if the company’s portfolio includes the XJ650 Turbo motorcycle, which has become perhaps the most massive among all this honest turbo company – in 1982 and 1983 the company managed to produce about 8000 copies.

In the 21st century, a bike with a skinny fork, comical 266mm brake discs up front and a design that seems a little naive, evokes the same feelings and emotions that arise when watching action games of the eighties. But the engineering part does not tolerate condescending smiles. The 653cc air-cooled inline four-cylinder engine with four Mikuni carburetors used a Mitsubishi supercharger with a compact 39mm turbine wheel.

Possessing less inertia and developing a pressure of only 0.5 bar, he brought the return to 90 hp. at 9000 rpm and at least made the traction control more predictable and comfortable. Interestingly, the motor had an exhaust tract on each side, but in fact “exhaled” through its left side. The right one was given to the wastegate department.

The Turbo’s frame and steering are virtually identical to those of the standard XJ650 Seca, minus the fairing, turbo, and other goodies of life. Among the differences are a modified fork and four-adjustment rear shock absorbers, which, according to Cycle, created a handling miracle. It was also noted that the weighty Yamaha with a curb weight of over 250 kg felt much lighter than Honda’s turbobikes.

The last production bike to hit the road on a supercharged wave was the 1983-1985 Kawasaki GPz750 Turbo. And this is again very symbolic – the company put an end to the measurements of “snails”, releasing one of the fastest motorcycles, which managed to effortlessly go around much larger atmospheric equipment.

However, in this case, it is not even the presence of a turbocharger in a 738-cc four-cylinder air vent with a fuel injection system that is interesting, but its location. Engineers placed the Hitachi compressor not behind the engine, but in front – as close as possible to the exhaust windows. The layout reduced turbo lag and improved throttle response. A moderate boost pressure of 0.7 bar was sufficient to produce 112 hp. at 9000 rpm and a powerful pickup over 5000 rpm, a top speed of over 230 km/h and a ¼ mile in 10.9 seconds.

Journalists who compared the Kawasaki with the same Yamaha XJ650 Turbo noted a significant superiority in dynamics, but did not forget to mention that the creation of “crossed tuning forks” is more comfortable and softer.

Obviously, turbocharging has not yet said its weighty word in modern motorcycle technology. But its return won’t herald the birth of monsters – rather, riders will get a medium-sized machine with “litre” torque, which allows you to forget about the gearbox, and convenient traction control. Well, for wildness it is better to turn to the tuners.